One thing that always intrigued me about ML is that the more you learn about it the more you realize how little you know. One such case that happened to me a few months ago when a person asked me if I could help him in SVM and me being me I was like sure not a big deal. It was a big deal.

Most of us might be familiar with training models. Few of us might be familiar with when to use which model. But when it comes to the details of these models we might fail to utilize them. In SVM, most of us might use the default RBF, a few of us might play with other kernels to find a better model and chosen ones might understand the working and purpose of these kernels. But can you create a kernel of your own?

Let’s go ahead and try to understand a bit about how you can create your own kernel and train a simple SVC model over it.

Getting Our Data

Every ML Pipeline is basically non-existent without data. So let’s start by getting our data. I’m a simple man so for the sake of simplicity I’ll just make a dataset using the make_classification utility in sklearn.datasets.

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

x,y = make_classification(n_samples = 1000)

print(x.shape, y.shape)

Now that we have the data all sorted out let’s go ahead and understand about working and use of kernels in SVM.

Understanding Kernels

To those who forgot how SVM works, which is nothing to worry about, let’s take a walk down the memory. So basically what SVM aims to do is to introduce a hyperplane that divides the data such that the margin by which they are separated is maximized but if you just what to maximize the margin then you might run into cases where its impossible to maximize the margin or even worse outliers affecting the margin size.

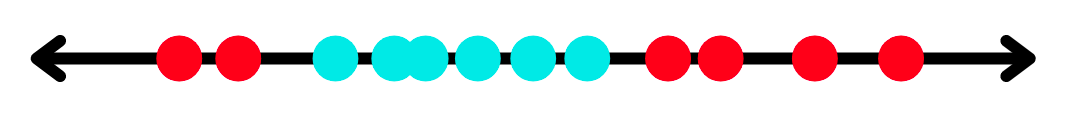

So to tackle this we ignore some points and allow the error in order to achieve optimal margin, we call these points support vectors. And now the margin is called a soft margin. So your aim is to maximize the soft margin. How much misclassification to allow is determined using cross-validation. This is a nice approach until you run into something I call a not so simple distribution. Take a look at the following not so simple example:-

So as you can see you can’t really separate the above distribution decently with a single hyperplane. But this is where things become interesting, if you map this distribution to a higher dimension you’ll be able to do the same. This is where kernels come into play these are mathematical functions that map your distribution to a higher dimension. But these kernel functions only compute the relationship of pair in the distribution as if they were in a higher dimension without actually transforming it and this trick to compute relationships in distribution at higher dimension without transforming it is what we call a kernel trick.

Phew, that was a lot of complicated stuff. But how does RBF work? RBF actually maps the data into infinite dimensions, which makes it difficult to visualize. So let’s keep that for another article.

So now that we have a bit of an understanding of the use of kernels in SVM let’s learn about how we can use a custom one in training them.

My Kernel, My Rules

Every time you create an SVC() instance it has a kernel associated with it that handles the mapping part, if you don’t specify it explicitly then it takes the kernel as RBF with looks like the following:-

$$ K(x_i,x_j) = e^{-{\gamma}||x_i-x_j||^2} ,{\forall}{\gamma} > 0 $$

$$ ||x_i-x_j||{\space}is{\space}the{\space}euclidean{\space}distance{\space}between{\space}x_i{\space}and{\space}x_j $$

If you don’t understand what’s written above then it’s fine you can forget it. The important thing to understand is how it works it takes 2 points and computes the RBF for them and stores them in their location in a gram matrix. Gram Matrix is what we’ll use to define relationships among pairs for the given kernel. Now 2 ways to train SVM over custom kernel is to:-

- Passing the kernel function

- Passing Gram Matrix

For the innocent souls who are unaware of Gram Matrix, it is basically how your kernel functions are represented, simple as that. If you wanna go into the mathematical details for it feel free to Google.

By passing the kernel function as an argument

Let’s now implement a simple Linear Kernel Function and train our model over it. Linear Kernel looks like the following:-

$$ K(x_i,x_j) = x_i \cdot x_j $$

Simple right? All you have to do is just perform a dot product between the pairs. Let’s create a function to do the same.

def linear_kernel(x_i, x_j):

return x_i.dot(x_j.T)

That was simple, wasn’t it? Let’s go ahead and create 2 classifiers one that uses the linear kernel defined in sklearn and the other that we created and then compare their performance.

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

clf1 = SVC(kernel = linear_kernel)

clf1.fit(x,y)

print(f'Accuracy on Custom Kernel: {accuracy_score(y, clf1.predict(x))}')

clf2 = SVC(kernel = 'linear')

clf2.fit(x,y)

print(f'Accuracy on Inbuilt Kernel: {accuracy_score(y, clf2.predict(x))}')

Output:-

Accuracy on Custom Kernel: 0.961

Accuracy on Inbuilt Kernel: 0.961

Well, the results are the same. That was pretty awesome, wasn’t it? Now let’s try doing the same using the 2nd method.

By passing Gram Matrix

You can define your own kernels by either giving the kernel as a function, as we saw in the above example, or by precomputing the Gram matrix. We’ll first make a function that makes gram matrix given data and function and then make function to compute RBF.

import numpy as np

def get_gram(x1, x2, kernel):

return np.array([[kernel(_x1, _x2) for _x2 in x2] for _x1 in x1])

def RBF(x1, x2, gamma = 1):

return np.exp(-gamma*np.linalg.norm(x1-x2))

Now that we have pre-requisites all set let’s train our models and compare. Two things that’ll change is:-

- We’ll pass kernel = ‘precomputed’

- We’ll pass the data as gram matrix while passing data in fit() or predict() function

Now things are a bit different if you have a testing set. For example, if we have x_train and x_test then gram matrix to pass in fit() is computed between x_train and x_train but for predicting on x_test it is computed between x_test and x_train.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

x_train, x_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(x, y, stratify = y)

def get_gram(x1, x2, kernel):

return np.array([[kernel(_x1, _x2) for _x2 in x2] for _x1 in x1])

def RBF(x1, x2, gamma = 1):

return np.exp(-gamma * np.linalg.norm(x1-x2))

clf1 = SVC(kernel = 'precomputed')

clf1.fit(get_gram(x_train, x_train, RBF), y_train)

print(f'Accuracy on Custom Kernel: {accuracy_score(y_test, clf1.predict(get_gram(x_test, x_train, RBF)))}')

clf2 = SVC(kernel = 'rbf')

clf2.fit(x_train,y_train)

print(f'Accuracy on Inbuilt Kernel: {accuracy_score(y_test, clf2.predict(x_test))}')

Output:-

Accuracy on Custom Kernel: 0.912

Accuracy on Inbuilt Kernel: 0.904

Code

import numpy as np

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

x,y = make_classification(n_samples = 1000)

x_train, x_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(x, y, stratify = y)

# Method 1

def linear_kernel(x_i, x_j):

return x_i.dot(x_j.T)

clf1 = SVC(kernel = linear_kernel)

clf1.fit(x_train,y_train)

print(f'Accuracy on Custom Kernel: {accuracy_score(y_test, clf1.predict(x_test))}')

clf2 = SVC(kernel = 'linear')

clf2.fit(x_train, y_train)

print(f'Accuracy on Inbuilt Kernel: {accuracy_score(y_test, clf2.predict(x_test))}')

# Method 2

def get_gram(x1, x2, kernel):

return np.array([[kernel(_x1, _x2) for _x2 in x2] for _x1 in x1])

def RBF(x1, x2, gamma = 1):

return np.exp(-gamma * np.linalg.norm(x1-x2))

clf1 = SVC(kernel = 'precomputed')

clf1.fit(get_gram(x_train, x_train, RBF), y_train)

print(f'Accuracy on Custom Kernel: {accuracy_score(y_test, clf1.predict(get_gram(x_test, x_train, RBF)))}')

clf2 = SVC(kernel = 'rbf')

clf2.fit(x_train,y_train)

print(f'Accuracy on Inbuilt Kernel: {accuracy_score(y_test, clf2.predict(x_test))}')

Parting Words

Well, how about that our kernel actually performed well. Noice! Now you know how you can train SVM over a custom kernel. You can try and implement other kernels like Thin-Plate, Cauchy, and other kernels with intimidating names. Using custom kernels isn’t usually done practically and in my experience, it’s probably because custom ones take a lot of time to train and predict especially if you go with the gram matrix approach. But there is no harm in learning about it right? With this, I congratulate you on learning something new and now you can go ahead and try one yourself. The next article is gonna be especially interesting it’s about probably the most popular algo but with a twist of our own. See you soon.